WORDS Hans Tammemagi

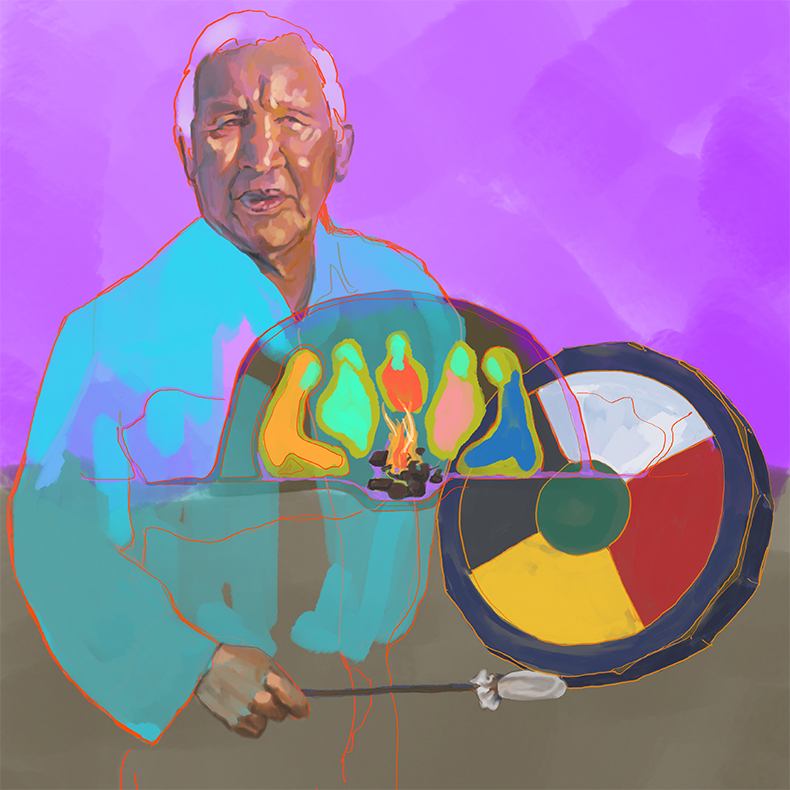

Illustration Sierra Lundy

My eyes were wide open, but it was utterly black with not the tiniest sliver of light. And it was intensely hot. Drums pounded, reverberating like the heartbeat of some giant beast. Then a deep guttural voice started singing in unknown words.

This was far from the golf I had come to play at Talking Rock Golf, Quaaout Lodge’s championship course beside Little Shuswap Lake near Chase, BC. The Little Shuswap Indian band owns and operates the resort.

Last night I met Ernie, an Elder with a creased leathery face and long grey hair in a ponytail. Beating a drum, he sang an Indigenous song of welcome and then said, “I want you to join us in a sweat. We can’t expect white people to understand us unless you experience our traditions.”

I hesitated in accepting. After all, my goal was to lower my handicap. But I agreed to join them.

The morning arrived, and there were three now: Ernie; Chief Felix, a slim dark-haired man with a shy manner; and Denny, a Cree man. After changing into swimming trunks, we crawled through a narrow tunnel into the sweat lodge, a circular pit house about 10 feet in diameter and four feet high with a fire in the centre. Sitting on skins, we leaned against cedar walls.

“Welcome to the oldest church on Earth,” said Ernie. “Today is a prayer sweat.”

An infrequent church-goer, I hoped it would finish in time to squeeze in 18 holes. Denny brought in six red-hot rocks and darkness settled over us.

Chief Felix explained, “These rocks represent the four quadrants of Earth.”

He sprinkled sage on the rocks and an earthy aroma drifted over us. He thanked the rocks and splashed water on them.

As the temperature rose, he spoke confidently from the darkness: “In the sweat we are all equals. We must open up our minds and seek ways to become closer with the Earth and all those around us.

“We will go around the stones four times. First, we will pray for ourselves. On the second round we will pray for women. Then for men and finally to give thanks.”

He started by praying to the Creator to make him a better person and to give him wisdom in guiding his people.

Although I sat just a few feet from the others, in the blackness I felt a thousand miles removed. And it was so different from the ritual of any church I had ever attended.

Elder Ernie was next and he spoke of his youth in residential school and how his anger toward the white man led him to alcohol and drugs. He thanked the Creator for releasing him from addiction and prayed the Creator would channel goodness through his heart. Then he spoke in his ancestral tongue and sang in a deep bass tone while beating his drum. Denny’s drum joined in, and the small space echoed with loud thumping.

It was my turn. At first it was difficult, but the darkness was comforting. I recognized that I am a driven person, always needing to keep busy. I don’t spend enough time with family and friends. The sweat was taking me down paths I normally never tread.

As I spoke, my thoughts began to pour forth. I described a friend who suffers from depression. I asked the Creator to offer him compassion, and to make me slow down and take time to support him.

Denny brought in six more hot rocks, and it became even hotter. After the second round of prayers, we took a break and crawled out, moving clockwise around the fire pit. Outside, the glaring sun made us shield our eyes. After a quick plunge into the cool lake, we re-entered the blackness.

The chief prayed for two women, one who is addicted to drugs and alcohol and the other who is single with three children. The prayers of my companions reflected the Indigenous philosophy of kindness and closeness to mother Earth.

It was my turn again. It was painful but I forced myself to speak of my mother who passed away at age 57 from a cancerous lung. I owe her so much and so much was left unsaid. I spoke of a lady friend who is a closet alcoholic. What demons chase her? Drums beat and echoed in the small space. Thoughts that had long gathered dust skittered around in my mind.

Sweat trickled into my eyes and down my back. Occasionally, we passed a wooden bucket of water from one to another, clumsily, like blind men. Splashing water on my head brought momentary relief. Drums pounded and echoed.

A fresh round of prayers began. I spoke of a young relative who has an anger problem that is threatening his marriage. Where does his anger come from? My companions gave thanks to social workers, friends and the police who play important roles in their community.

My invisible companions and I were from different societies, but in the darkness we were together as one. Yesterday we were strangers, but now I was sharing confidences with them that I had never discussed with anyone else. Their church has an awesome power.

The chief closed the ceremony with “All my relations.”

As we emerged, I felt cleansed and rejuvenated. I strode past the golf course without a glance. I needed to call my wife and children and tell them I loved them.

Music City

Music City